As pointed out in the previous post, there is a healthy amount of aid literature. Though often insightful and interesting, these works are pretty inaccessible to the general public and not exactly the sort of thing you would relax to on your sofa with a cup of tea.

So what about aid fiction? Or, in fact, anything creative produced about the aid world?

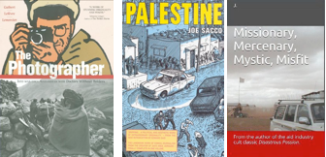

‘Emergency Sex’ by Kenneth Cain et. al. is perhaps the first that springs to mind – though as fictionalised memoirs, I’m not sure this entirely counts. There is a forest of aid blogs scattered throughout the internet (yours truly included) – though again, most are first-person reflections and none fictional or purely creative. Some films and books do address aid work, but most incidental to the main narrative – such as Hotel Rwanda or Joe Sacco’s ‘Palestine’. The only purely fictional creative works that I can think of off the top of my head are the recent book ‘Missionary, Mercenary, Mystic, Misfit’ by blogger J of SEAL, the beautiful graphic novel ‘The Photographer’ about photographer Dider Lefevre’s journey with MSF in Afghanistan, and Jane Bussmann’s comedy show ‘Bono and Geldof are C***ts’. All fantastic, but three is still a rather sad total. If I’ve missed anything blindingly obvious then please do send suggestions through and lets boost this meagre selection – but I still suspect it will not be enough to establish a full-blown genre.

Isn’t this completely baffling? For anyone who has spent any length of time in ‘the field’, it must be apparent that the creative material open to us is extraordinarily rich. You meet characters that even David Lynch would struggle to invent and government systems so positively Kafkaesque, they would be hilarious if they weren’t so terrifying. Some of the stories I’ve heard booted around bars and in compounds over a few beers defy the wildest imaginations and occasionally the laws of physics, and are so totally mad you just couldn’t make them up – such as the character (lets call him Mad Greg) who, back in the day, was in charge of a Sudanese hospital and formed a local paramilitary to blow a couple of his staff out of jail, and later holed up under siege in the hospital. Wouldn’t it be great if someone was writing this down?

The stage that we all perform on – the situations of war and violence where aid is made necessary should force powerful questions about the nature of being human in our modern world. As aid workers we peddle in the trade of death and life, bearing a dual blessing of being privy to the best and the absolute worst of humanity. And yet the acute frustration borne of impotence and insufficiency in the face of awful suffering, seems, for the moment, only to be expressed through blogs or formalised introspection. For centuries, the savage brutality of war has inspired legions of soldiers to write, draw, paint and put to music their experiences. So why are we so quiet?

Perhaps the sheer trove of possibility is simply too overwhelming, or too outrageous. Or perhaps everyone is just too busy.

Which is a shame, because a vibrant and critical artistic lens is, I think, a sign of maturity. A way of being able to question, poke fun at and expose an imperfect system to a public audience, in a way that isn’t clouded with impenetrable industry jargon.

So I reckon what the aid sector really needs is a proper, explosive call to arms. No more dry academic discourse, no more roundtable navel-gazing…

Frustrated with head office requesting the millionth round of corrections on a proposal? Screw them! Write a poem! Being forced to quietly toe the line as you watch a government abuse its citizens with impunity – just so you can keep that health clinic running? Pull out a paintbrush, create something epic! Felt that catch in your throat when you spoke with a mother and she told you quietly, proudly, that her child lives because of your emergency feeding programme – and you remembered why it is you do this job and that it is never enough but it is something. You, why are you so silent?

And if we aren’t honest about our failures, our struggles, then how on earth can we celebrate our successes?

So yeah, why not try and move beyond this narrow box of policy reports, blog posts and ironic Twitter updates that has become the only channel for frustration, discontent and joy.

Let’s see the initial weeks of a first phase response played out as a full-scale opera. Wagnerian overtures as helicopters chopper in emergency medical supplies … and then have to dump the load because someone screwed up the cold chain (whilst a chorus of chattering media/comms types gleefully exclaim the events in falsetto). Or perhaps a Sopranos-style sitcom set in the backwaters of some field base, where coordination meetings are ruled by OCHA’s answer to James Gandolfini…

You get the picture. Let’s do it!