There are three certainties in life. The first two are death and taxes. The third – known only to monitoring and evaluation (M&E) practitioners – is that during any workshop on M&E, someone will smugly point out that we should be examining contribution, not attribution.

There are three certainties in life. The first two are death and taxes. The third – known only to monitoring and evaluation (M&E) practitioners – is that during any workshop on M&E, someone will smugly point out that we should be examining contribution, not attribution.

Those of you without experience in M&E jargon (lucky you!) will need a bit of help at this point. “Attribution” is the idea that a change is solely due to your intervention. If I run a humanitarian programme dedicated to handing out buckets, then the gift of a bucket is ‘attributable’ to my programme. I caused it, and nobody can say otherwise. “Contribution” is the idea that your influence is just one of many factors which contribute to a change. Imagine that I was lobbying for a new anti-corruption law. If that law passes, it would be absurd to say that I caused it directly. Lots of factors caused the change, including other lobbyists, the incentives of politicians, public opinion, etc. The change is not ‘attributable’ to me, but I ‘contributed’ to it.

There are two reasons why it is a mistake to emphasise contribution. Firstly, it’s far too often used as a get-out clause. The phrase “we need to assess contribution, not attribution” is typically used to mean “Something good has happened. We want to imply that it was thanks to us, without trying to work out exactly how.” Even if you’re assessing contribution, you still need to understand the extent to which you contributed, and the process through which this happened. Of course, the contribution gurus understand this. All too often, however, their disciples just use contribution as an excuse to avoid doing any actual thinking.

This reflects a fundamental misconception that, if you look at contribution, you no longer need to examine the counterfactual. (The counterfactual, for the by-now-bewildered non-M&E folk, is the question of what would have happened if your programme had not existed.) Of course, it is not always possible to quantitatively assess the counterfactual, in the way that randomised control trials (RCTs) do. But it is always a valid thought-experiment, and an essential part of good M&E. If you’re not thinking about the counterfactual, then you’re simply not asking whether your programme really needed to be there.

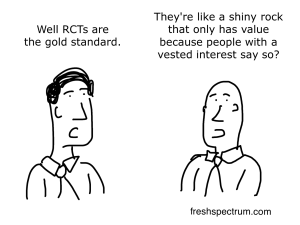

Secondly, the term ‘contribution’ itself is used to mean multiple, often inconsistent things. The common-sense meaning of contribution, as defined above, is that there were many factors that caused the observed change. This is completely unhelpful. Any change (except for the most simple) is caused by many things. An RCT – often seen as the gold-standard way to assess attribution – recognises that many factors caused the measured outcomes. That’s why you use a RCT in the first place. Consequently, this meaning of ‘contribution’ does not justify the methodological differences that this approach implies.

A more useful definition of ‘contribution’ is that the change is not possible to measure quantitatively, or is a binary change (like a law being passed). In this case, it is not possible to ‘attribute’ a certain percentage of the change to your intervention. To illustrate the point, consider two different outcomes; (1) increased yield, (2) the passing of a law, and (3) a change in societal values. The first one is quantitative and divisible – it makes sense to talk of a percentage of a change in yield. Consequently, we can speak of an ‘attributable’ change in yield. The second and third, by contrast, don’t’ lend themselves to quantitative breakdown. It does not make sense to pass a percent of a law – it either passes or it doesn’t. Consequently, trying to work out what percentage of a new law is ‘attributable’ to your organisation is simply nonsensical. Similarly, you could never assign a percentage to the extent to which societal values change. In the latter two cases, consequently, it makes sense to talk of contribution rather than attribution.

In every case, however – whether ‘attribution’ or ‘contribution’ – the basic question is the same; what difference did the intervention make? How did it make this difference, and what other factors were relevant? Whether you can quantify the difference or not is a methodological detail, but doesn’t affect the basic question that you are asking. Looking at contribution, consequently, is a red herring.

Reblogged this on Impact Peace.