Author: Nadeem Ul Haque, Former Deputy Chairman Planning Commission of Pakistan

Ghari Baqir* returned to Pakistan with a PhD from Harvard 3 decades ago: keen to use his new-found skills to contribute to policy and thought in his homeland. Teaching at university provided an opportunity to do research, write books and perhaps at some stage advise the Government. He had ideas and wanted to work hard.

Soon he realized that professors were at the bottom of the barrel. In a society where power and wealth is everything, he had neither. His counterparts in the bureaucracy had power and healthy perks and plots, whereas all he had was a measly salary, no power, no perks. His tiny filthy office did not even have a phone (in that era before cellphones).

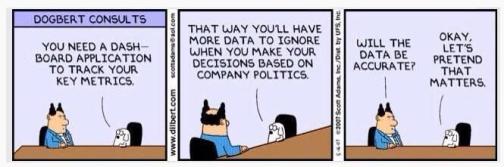

Luckily, donors offered him paid consulting opportunities and eventually he made enough money to buy his own house. In the process, sadly, dreams of independent research; his bright ideas; those books he wanted to write, were buried. Donor consulting meant working on someone else’s agenda. He wrote long, lengthy and often meaningless reports on poorly thought out projects. He reported to junior donor officials as well as their contractors who controlled money with little originality. The terms were very clear: Ghari could only dance to their tune.

Ironically he was discriminated against. He was always paid ‘domestic’ rates which usually were half of what international consultants who worked with him got. Even though the international consultants were often not as well qualified as him. “Discriminated against in my own country” he says, “but who do I turn to?”

“So hungry is the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and External Affairs Division (EAD) for donor money, that they do not even question donor practices, quality or agendas.” His concerns received a deaf ear from EAD.

10 years later, his growing business allowed him to create a consulting firm in Islamabad. The firm grew and became very close to two of the biggest donors, as well as a subcontractor for major US consulting firms. Money was finally coming in.

However, the growth soon peaked. Donors didn’t give him the opportunity to compete with their own consulting firms. He knew the heads of these firms well and was well aware he could do as good as, and probably a better job than them. But fine print in the rules prevented him from competing. So he remained the junior partner, sometimes even just a mere logistics supplier.

For example, when X Consulting from Washington DC won a 100 million USD contract, his firm received just 3 million USD, despite doing the majority of the work. But X Consulting’s costs were higher, their consultants flew in and lived in 5 star hotels from where they instructed Ghari’s team.

He thought about expanding overseas but he could not compete with Western consultancies who had huge support from their home regulatory systems, and were the favourites of donors in all markets.

When last we met, Ghari told me that there could never be a Pakistani consulting firm of an international level in this sector as the game is loaded against us. I tried to encourage him by using cars as an example of where our Government has provided protection for national companies. I also told him about the National Tariff Commission which guards all industry in Pakistan from dumping practices. Their website shows ongoing investigations into Polythene, Soda Ash and garments for allegations of dumping as well as successful historical investigations. Then there is the Competition Commission which looks into anticompetitive practices and has taken stands in sugar and cement industries.

Following our conversation, Ghari marched off to all these agencies to plead his case. He had a hard time explaining what an ‘intellectual industry’ was. Everyone can see and use cars, but not thought.

Ghari had come full circle—starting out as a professor in a society where education and research had no value to becoming a sort of ‘thought’ entrepreneur in an environment where intellectual work is routinely subject to dumping by donors.

Even his original ideas do not belong to him. Consultants and donor agencies get the citation. Ghari is merely the ghost in the machine. As he would tell you himself, “History and our country’s experience has abundantly illustrated that development is a direct product of better ideas arising from thought and research. Yet in Pakistan, the Government unintentionally facilitate dumping on our ‘thought’ industry. It would seem they are marching to the tune of defunct economists.”

* The individual’s name has been changed to protect them.

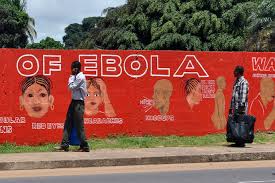

inated water is a norm and no-one blinks when asked to have their temperature tested before entering a building. In fact, one of the most popular games seems to be ‘guess my precise temperature’ before being told.

inated water is a norm and no-one blinks when asked to have their temperature tested before entering a building. In fact, one of the most popular games seems to be ‘guess my precise temperature’ before being told.